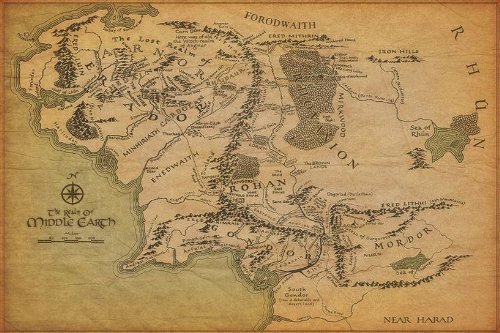

The next chapter offers us a contrast – an opening section, in which the traveler wanders in the wilderness, followed by an encounter with the city Tamara.

The hallmark of wilderness is that it is insignificant. Consider that word for a moment. What does it mean? “Unimportant”? Perhaps rather, “not signifying”?

You walk for days among trees and among stones. Rarely does the eye light on a thing, and then only when it has recognized that thing as the sign of another thing: a print in the sand indicates the tiger’s passage; a marsh announces a vein of water; the hibiscus flower, the end of winter. All the rest is silent and interchangeable; trees and stones are only what they are.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, Cities & Signs 1

The eye only rests on things which it can make sense of, when a thing seems to be “the sign of another thing.” How would we make sense of rocks, trees, the forest without the linguistic signifiers we have for them? When Kant defined the sublime, he described how we encounter natural things that dwarf us (a thunderstorm, a mountain, a canyon) and mentally experience a kind of shrinking of those things – they fail to hurt us, we take something large (a massive rift eaten into the earth of the desert) and we make it small through thought, through naming it: we call it “The Grand Canyon” but the act of naming itself makes us grander than the canyon. Nothing is only what it is, to us. We can only recognize things when they function as signs; signs both reveal and obscure – reveal because without a sign, things are invisible, insignificant, but the signs themselves also stand in front of and replace what we encounter. Thus Walker Percy, in his essay “The Loss of the Creature,” describes all the images, postcards, signs that come between us and our experience of the Grand Canyon.

Image source: https://www.nps.gov/grca/index.htm

And then the traveler enters Tamara, a city of endless signs:

You penetrate it along streets thick with signboards jutting from the walls. The eye does not see things but images of things that mean other things: pincers point out the tooth-drawer’s house; a tankard, the tavern; halberds, the barracks; scales, the grocer’s. Statues and shields depict lions, dolphins, towers, stars: a sign that something—who knows what?—has as its sign a lion or a dolphin or a tower or a star. Other signals warn of what is forbidden in a given place (to enter the alley with wagons, to urinate behind the kiosk, to fish with your pole from the bridge) and what is allowed (watering zebras, playing bowls, burning relatives’ corpses). From the doors of the temples the gods’ statues are seen, each portrayed with his attributes—the cornucopia, the hourglass, the medusa—so that the worshiper can recognize them and address his prayers correctly. If a building has no signboard or figure, its very form and the position it occupies in the city’s order suffice to indicate its function: the palace, the prison, the mint, the Pythagorean school, the brothel. The wares, too, which the vendors display on their stalls are valuable not in themselves but as signs of other things; the embroidered headband stands for elegance; the glided palanquin, power; the volumes of Averroes, learning; the ankle bracelet, voluptuousness. Your gaze scans the streets as if they were written pages: the city says everything you must think, makes you repeat her discourse, and while you believe you are visiting Tamara you are only recording the names with which she defines herself and all of her parts.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, Cities & Signs 1

However the city may really be, beneath this thick coating of signs, whatever it may contain or conceal, you leave Tamara without having discovered it. Outside, the land stretches, empty, to the horizon; the sky opens, with speeding clouds. In the shape that chance and wind give the clouds, you are already intent on recognizing figures: a sailing ship, a hand, an elephant…

Everything is represented by a sign – the barber pole we have learned means haircut, the circle minus a wedge that reads pizza. As Calvino describes, signs represent places and things; they classify activities into allowed and forbidden (think of restroom iconography; a triangle signifies womanhood, and unleashes a whole range of gendered ideas)

Image credit: https://www.homedepot.com/p/Lynch-Sign-8-in-x-8-in-Blue-Plastic-with-Braille-Restroom-Sign-UNI-18/202392882

Placement, too, is iconography: “If a building has no signboard or figure, its very form and the position it occupies in the city’s order suffice to indicate its function: the palace, the prison, the mint, the Pythagorean school, the brothel.”

And items sold are signs as well. Green paper represents wealth, value. Clothing, shoes, accessories represent types of people, social classes. Think of the ways that yoga pants have come to signify a certain kind of middle class lifestyle, the way that having a piano in your living room once meant that your family was middle class, that the women had the leisure to learn to play piano. Now they have the leisure to exercise, and yoga represents the most virtuous of all kinds of exercise, with its vaguely spiritual connotations.

As Calvino presents it here, as we live it every day, we live in a world of signs, in a mediated world. Growing up is a process of learning (and being taught) to read these signs appropriately, so that we can maneuver our way through our lives, our culture, seamlessly. It is important not to see things as they are.